Don’t be a show-off. Never be too proud to turn back. There are old pilots and bold pilots, but no old, bold pilots.

I first heard the latter part of this famous quote made by US Airmail Pilot E. Hamilton Lee back when I raced cars. At that time, one of the better drivers in town, Gordon Monroe, used a variant of that quote (with pilots replaced by racers) when giving me driving advice. Gord’s basic message was that it is impossible to win a race if you crash out of it.

Nearly all of us have taken the odd chance and made some decisions that, in retrospect, just didn’t make sense from a risk vs reward perspective. Age and experience clearly helps but mistakes still get made and none of us are exempt. Most people’s mistakes at work don’t have life safety consequences and their mistakes are not typically picked up widely by the world news services as was the case in the recent grounding of the Costa Concordia cruise ship. But, we all make mistakes.

I often study engineering disasters and accidents in the belief that understanding mistakes, failures, and accidents deeply is a much lower cost way of learning. My last note on this topic was What Went Wrong at Fukushima Dai-1 where we looked at the nuclear release following the 2011 Tohuku Earthquake and Tsunami.

Living on a boat and cruising extensively (our boat blog is at http://blog.mvdirona.com/) makes me particularly interested in the Costa Concordia incident of January 13th 2012. The Concordia is a 114,137 gross ton floating city that cost $570m when it was delivered in 2006. It is 952’ long, has 17 decks, and is power by 6 Wartsila diesel engines with a combined output of 101,400 horse power. The ship is capable of 23 kts (26.5 mph) and has a service speed of 21 kts. At capacity, it carries 3,780 passengers with a crew of 1,100.

From: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Costa_Concordia_disaster:

The Italian cruise ship Costa Concordia partially sank on Friday the 13th of January 2012 after hitting a reef off the Italian coast and running aground at Isola del Giglio, Tuscany, requiring the evacuation of 4,197 people on board. At least 16 people died, including 15 passengers and one crewman; 64 others were injured (three seriously) and 17 are missing. Two passengers and a crewmember trapped below deck were rescued.

The captain, Francesco Schettino, had deviated from the ship’s computer-programmed route in order to treat people on Giglio Island to the spectacle of a close sail-past. He was later arrested on preliminary charges of multiple manslaughter, failure to assist passengers in need and abandonment of ship. First Officer Ciro Ambrosio was also arrested.

It is far too early to know exactly what happened on the Costa Concordia and, because there was loss of life and considerable property damage, the legal proceedings will almost certainly run for years. Unfortunately, rather than illuminating the mistakes and failures and helping us avoid them in the future, these proceedings typically focus on culpability and distributing blame. That’s not our interest here. I’m mostly focused on what happened and getting all the data I could find on the table to see what lessons the situation yields.

A fellow boater, Milt Baker pointed me towards an excellent video that offers considerable data into exactly what happened in the final 1 hour and 30 min. You can find the video at: Grounding of Costa Concordia. Another interesting data source is the video commentary available at: John Konrad Narrates the Final Maneuvers of the Costa Concordia. In what follows, I’ve combined snapshots of the first video intermixed with data available from other sources including the second video.

The source data for the two videos above is a wonderful safety system called Automatic Identification System. AIS is a safety system required on larger commercial craft and also used on many recreational boats as well. AIS works by frequently transmitting (up to every 2 seconds for fast moving ships) via VHF radio the ships GPS position, course, speed, name, and other pertinent navigational data. Receiving stations on other ships automatically plot transmitting AIS targets on electronic charts. Some receiving systems are also able to plot an expected target course and compute the time and location of the estimated closest point of approach. AIS an excellent tool to help reduce the frequency of ship-to-ship collisions.

Since AIS data is broadcast over VHF radio, it is widely available to both ships and land stations and this data can be used in many ways. For example, if you are interested in the boats in Seattle’s Elliott Bay, have a look at MarineTraffic.com and enter “Seattle” as the port in the data entry box near the top left corner of the screen (you might see our boat Dirona there as well).

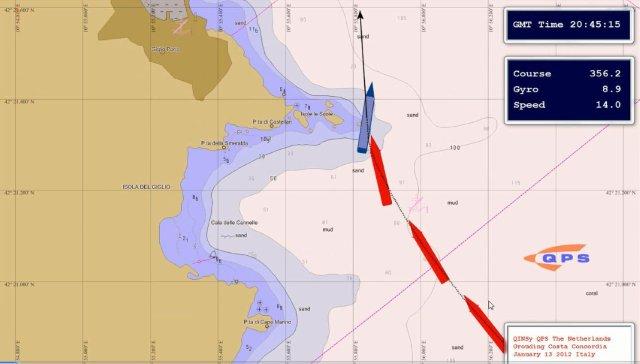

AIS data is often archived and, because of that, we have a very precise record of the Costa Concordia’s course as well as core navigational data as it proceeded towards the rocks. In the pictures that follow, the red images of the ship are at the ship’s position as transmitted by the Costa Concordia’s AIS system. The black line between these images is the interpolated course between these known locations. The video itself (Costa Concordia Interpolated.wmv) uses a roughly 5:1 time compression.

In this screen shot, you can see the Concordia already very close to the Italian Isol del Giglio. From the BBC report the Captain has said he turned too late (Costa Concordia: Captain Schettino ‘Turned Too Late’). From that article:

According to the leaked transcript quoted by Italian media, Capt Schettino said the route of the Costa Concordia on the first day of its Mediterranean cruise had been decided as it left the port of Civitavecchia, near Rome, on Friday.

The captain reportedly told the investigating judge in the city of Grosseto that he had decided to sail close to Giglio to salute a former captain who had a home on the Tuscan island. “I was navigating by sight because I knew the depths well and I had done this maneuver three or four times,” he reportedly said.

“But this time I ordered the turn too late and I ended up in water that was too shallow. I don’t know why it happened.”

In this screen shot of the boat at 20:44:47 just prior to the grounding, you can see the boat turned to 348.8 degrees but the massive 114,137 gross ton vessel is essentially plowing sideways through the water on a course of 332.7 degrees. The Captain can and has turned the ship with the rudder but, at 15.6 kts, it does not follow the exact course steered with inertia tending to widen and straiten the intended turn.

Given the speed of the boat and nearness of shore at this point, the die is cast and the ship is going to hit ground.

This screen shot was taken is just past the point of impact. You will note that it has slowed to 14.0 kts. You might also notice the Captain is turning aggressively to the starboard. He has the ship turned to a 8.9 degrees heading whereas the actual ships course lags behind at 356.2 degrees.

This screen shot is only 44 seconds after the previous one but the boat has already slowed from 14.0 kts to 8.1 and is still slowing quickly. Some of the slowing will have come from the grounding itself but passengers report that they heard the boat hard astern after the grounding.

You can also see the captain has swung the helm over from the starboard course he was steering trying to avoid the rocks over to port course now that he has struck them. This is almost certainly in an effort to minimize damage. What makes this (possibly counter-intuitive) decision a good one is the ships pivot point is approximately 1/3 of the way back from the bow so turning to port (towards the shore) will actually cause the stern to rotate away from the rocks they just struck.

The ship decelerated quickly to just under 6.0 knots but, in the two minutes prior to this screen shot, it has only slowed a further 0.9 kts down to 5.1. There were reports of a loss of power on the Concordia. Likely what happened is ship was hard astern taking off speed until a couple of minutes prior to this screen shot when water intrusion caused a power failure. The ship is a diesel electric and likely lost power to its main prop due to rapid water ingress.

At 5 kts and very likely without main engine power, the Concordia is still going much too quickly to risk running into the mud and sand shore so the Captain now turns hard away from shore and he is heading back out into the open channel.

With the helm hard over the starboard with the likely assistance of the bow thrusters the ship is turning hard which is pulling speed off fairly quickly. It is now down to 3.0 kts and it continues to slow.

The Concordia is now down to 1.6 kts and the Captain is clearly using the bow thrusters heavily as the bow continues to rotate quickly. He has now turned to a 41 degree heading.

It now has been just over 29 min since the ship first struck the rocks. It has essentially stopped and the bow is being brought all the way back round using bow thrusters in an effort to drive the ship back in towards shore presumably because the Captain believes it is at risk of sinking so he is seeking shallow water.

The Captain continues to force the Concordia to shore under bow thruster power. In this video narrative (John Konrad Narrates the Final Maneuvers of the Costa Concordia), the commentator reported that the combination of bow thrusters and the prevailing currents where being used in combination by the Captain to drive the boat into shore.

A further 11 min and 22 seconds have past and the ship has now accelerated back up to 0.9 kts now heading towards shore.

It has been more than an hour and 11 minutes since the original contact with the rocks and the Costa Concordia is now at rest in its final grounding point.

The Coast Guard transcript of the radio communications with the Captain are at Costa Concordia Transcript: Coastguard Orders Captain to return to Stricken Ship. In the following text De Falco is the Coast Guard Commander and Schettino is the Captain of the Costa Concordia:

De Falco: “This is De Falco speaking from Livorno. Am I speaking with the commander?”

Schettino: “Yes. Good evening, Cmdr De Falco.”

De Falco: “Please tell me your name.”

Schettino: “I’m Cmdr Schettino, commander.”

De Falco: “Schettino? Listen Schettino. There are people trapped on board. Now you go with your boat under the prow on the starboard side. There is a pilot ladder. You will climb that ladder and go on board. You go on board and then you will tell me how many people there are. Is that clear? I’m recording this conversation, Cmdr Schettino …”

Schettino: “Commander, let me tell you one thing …”

De Falco: “Speak up! Put your hand in front of the microphone and speak more loudly, is that clear?”

Schettino: “In this moment, the boat is tipping …”

De Falco: “I understand that, listen, there are people that are coming down the pilot ladder of the prow. You go up that pilot ladder, get on that ship and tell me how many people are still on board. And what they need. Is that clear? You need to tell me if there are children, women or people in need of assistance. And tell me the exact number of each of these categories. Is that clear? Listen Schettino, that you saved yourself from the sea, but I am going to … really do something bad to you … I am going to make you pay for this. Go on board, (expletive)!”

Schettino: “Commander, please …”

De Falco: “No, please. You now get up and go on board. They are telling me that on board there are still …”

Schettino: “I am here with the rescue boats, I am here, I am not going anywhere, I am here …”

De Falco: “What are you doing, commander?”

Schettino: “I am here to co-ordinate the rescue …”

De Falco: “What are you co-ordinating there? Go on board! Co-ordinate the rescue from aboard the ship. Are you refusing?”

Schettino: “No, I am not refusing.”

De Falco: “Are you refusing to go aboard, commander? Can you tell me the reason why you are not going?”

Schettino: “I am not going because the other lifeboat is stopped.”

De Falco: “You go aboard. It is an order. Don’t make any more excuses. You have declared ‘abandon ship’. Now I am in charge. You go on board! Is that clear? Do you hear me? Go, and call me when you are aboard. My air rescue crew is there.”

Schettino: “Where are your rescuers?”

De Falco: “My air rescue is on the prow. Go. There are already bodies, Schettino.”

Schettino: “How many bodies are there?”

De Falco: “I don’t know. I have heard of one. You are the one who has to tell me how many there are. Christ!”

Schettino: “But do you realize it is dark and here we can’t see anything …”

De Falco: “And so what? You want to go home, Schettino? It is dark and you want to go home? Get on that prow of the boat using the pilot ladder and tell me what can be done, how many people there are and what their needs are. Now!”

Schettino: “… I am with my second in command.”

De Falco: “So both of you go up then … You and your second go on board now. Is that clear?”

Schettino: “Commander, I want to go on board, but it is simply that the other boat here … there are other rescuers. It has stopped and is waiting …”

De Falco: “It has been an hour that you have been telling me the same thing. Now, go on board. Go on board! And then tell me immediately how many people there are there.”

Schettino: “OK, commander.”

De Falco: “Go, immediately!”

At least 16 died in the accident and 17 were still missing when this was written (Costa Concordia Disaster).The Captain of the Costa Concordia, Francesco Schettino, has been charged with manslaughter and abandoning ship.

At the time of the grounding, the ship was carrying 2,200 metric tons of heavy fuel oil and 185 metric tons of diesel and remains environmental risk remains (Costa Concordia Salvage Experts Ready to Begin Pumping Fuel from Capsized Cruise Ship Off Coast of Italy). The 170 year old salvage firm Smit Salvage will be leading the operation.

All situations are complex and few disasters have only a single cause. However, the facts as presented to this point pretty strongly towards pilot error as the primary contributor in this event. The Captain is clearly very experienced and his ship handling after the original grounding appear excellent. But, it’s hard to explain why the ship was that close to the rocks, the captain has reported that he turned too late, and public reports have him on the phone at or near the time of the original grounding.

What I take away from the data points presented here is that experience, ironically, can be our biggest enemy. As we get increasingly proficient at a task, we often stop paying as much attention. And, with less dedicated focus on a task, over time, we run the risk of a crucial mistake that we probably wouldn’t have made when we were effectively less experienced and perhaps less skilled. There is danger in becoming comfortable.

The videos referenced in the above can be found at:

· Grounding of Costa Concordia Interpolated

· gCaptain’s John Konrad Narrates the Final Maneuvers of the Costa Concordia

If you are interested in reading more:

· http://www.masslive.com/news/index.ssf/2012/01/costa_concordia_salvage_expert.html

· http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-16620807

· http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-16620807

· http://news.qps.nl.s3.amazonaws.com/Grounding+Costa+Concordia.pdf

· http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Costa_Concordia

· http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Costa_Concordia_disaster

b: http://blog.mvdirona.com / http://perspectives.mvdirona.com

Peter, thanks for posting the video of the Google Earth simulation (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DhwW6FlL9ow). Its nice work and its amazing what Google Earth is can do.

–jrh

For a fully animated Google Earth 3D recreation of the final voyage of the Costa Concordia go to:

http://sketchup.google.com/3dwarehouse/details?mid=57e14f9b30152cb51f2b60986ab4327c

For a YouTube of the animation go to:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DhwW6FlL9ow

Good hearing from you Chad. Yes, you are right, Schettino has taken the Costa Concordia on a near identical path at least once in the past. Lloyds list has detailed diagrams of the previous approach back on August 14th of 2011. Worth checking out at: http://www.lloydslist.com/ll/sector/ship-operations/article389069.ece.

–jrh

It would be quite interesting to overlay the AIS data from the previous approaches to the island made by Captain Schettino with the one resulting in the accident. I wonder if that data is archived.

Simon, thanks for relaying your paragliding experience and the fatality statistics from that sport. As you point out, paragliding near misses are not tracked. However, civilian aviation does track near misses and the database is publicly available. In the US, this system is run by NASA to keep it separate from the US government enforcement arm, the FAA. You’ll find the Aviation Safety Reporting System at: http://asrs.arc.nasa.gov/

–jrh

I love the motorbikes 101 point Robert. The basic lesson shows up in different forms in just about all fields. In aviation, the FAA tracks near misses (Aviation Safety Reporting System) as a way to detect problems before a real accident that almost certainly will lead to lost of life. Both the US and the UK track near misses (probably other jurisdictions do as well) and there is evidence supporting this has contributed to safer civilian aviation.

Paragliding is a great source of evidence for the proverb — of about 4000 US pilots, about 1% report injuries each year, about .1% die each year (high variance, of course, given the small numbers). When you take into consideration how often most of those pilots probably fly in any given year, it’s a dismal statistic. That said, the experience promises to be unmatched. My choice to give it a try despite the danger was a rationalization based on statistics. The flight school I attended had witnessed just one fatal injury over decades of instruction: an overly confident Navy Seal had purportedly ignored instructions and fallen into his own wing. Statistics suggest that it’s the intermediates who are at greatest risk — so as a beginner, why not give it a shot?

While experience could be viewed as an enemy, those who survive their intermediate experiences to advance to the P5 level are the safest pilots on an accident per flight basis. Experience serves to weed out those who are inherently susceptible to complacency, gracefully teaches them when it’s okay to be complacent, or perhaps just scares those who survive near misses to grow out of what is a universal developmental stage of complacency.

Thing is, I don’t know how we can distinguish these, given the absence of "near miss" statistics, something I dearly wanted to know, enjoying my experience and wondering if a commitment to vigilance and conservative choices on when to fly, as evidenced by never experiencing a near miss, would be enough to reduce my risk to an acceptable level (I quit flying as an intermediate before any near misses or crashes). I’d like to see more data on the near misses before drawing conclusions on if experience is the cause of disaster or is merely the light that illuminates those who had no business being pilots in the first place. Two different conclusions, deserving very different treatments.

fwiw, http://www.ushpa.aero/safety/PG2010AccidentSummary.pdf

"As we get increasingly proficient at a task, we often stop paying as much attention. And, with less dedicated focus on a task, over time, we run the risk of a crucial mistake that we probably wouldn’t have made when we were effectively less experienced and perhaps less skilled. There is danger in becoming comfortable."

Motorbikes 101 :-)